Student loan debt burdens 44 million people in the United States. However for CEOs of student loan companies, or investors on Wall Street, student debt is a lucrative commodity to be bought and sold for profit.

Simply put, gambling isn't the way to go for your student loan repayment. 'I know that not everyone is as fortunate as us to have extra money each month, but there are ways that you can maximize what you do have,' Nick said. The most extravagant thing you have spent your student loan/grant on? How to fund university? Red Ed's thinking about banning fruit machines Postgrad loan Penalised for being from a poorer background? Gambling professionally and student finance Evicted from student house. How can I get money quickly?

Gambling With Student Loan Money Market

Corporations such as Navient, Nelnet, and PHEAA service outstanding student debt on behalf of the Department of Education. These companies also issue Student Loan Asset-Backed Securities (SLABS) in collaboration with major financial institutions like Wells Fargo, JP Morgan, and Goldman Sachs. For these firms and their creditors, debt isn't just an asset, it's their bottom line.

Investors holding SLABS are entitled to coupon payments at regular intervals until the security reaches final maturity, or they can trade the assets in speculative secondary markets. There is even a forum where SLABS investors can anonymously discuss their assets and transactions, free from unwanted public scrutiny.

Yet the financialization of student debt is almost never reported on in the media. There is little public awareness that when student borrowers sign their Master Promissory Notes (affirming that they will repay their loans and 'reasonable collection costs'), their debts may be securitized and sold to investors.

The history of SLABS

SLABS resulted from specific federal policy decisions. On November 27, 1992, the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted Rule 3(a)(7) of the Investment Company Act of 1940, which allows companies who issue asset backed securities to be exempt from the legal definition of an 'investment company.' This exemption permits companies to avoid asset registration fees and regulatory oversight—making it profitable for student loan companies (among others) to issue securities, which effectively created the market for SLABS. In total, $600 billion worth of SLABS have been issued, with $170 billion worth still outstanding.

There are two main types of SLABS: those backed by loans made by private lenders, and those backed by loans made through the Federal Family Education Loan program (FFEL). The majority of all student debt today is the $1.1 trillion loaned by the federal government through the Direct Lending program. While these loans cannot be securitized directly, they can be if borrowers consolidate or refinance their loans through a private lender.

Private student loan debt accounts for roughly $120 billion of the $1.6 trillion total outstanding debt. Companies such as SoFi refinance student loans, and have issued $18 billion in SLABS since their founding in 2011. These loans are highly favorable to lenders—as borrowers who default on private loans face greater consequences than those who default on federal loans.

FFEL loans are made by private lenders that are guaranteed by the federal government if borrowers default, which incentivizes riskier lending. Although Congress ended the program in 2010, there are still roughly $280 billion of FFEL loans outstanding, and the largest firms such as Navient and Nelnet retain FFEL loans in their portfolios and have continued to issue FFEL-backed SLABS.

The next bubble?

Over the past few decades, student loan companies and Wall Street have amassed record profits. Meanwhile, $1.6 trillion of student debt is crushing generations of Americans by delaying home ownership, causing generational wealth to decrease, and contributing to widespread depression and even suicide. Since the ironically-named Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, student debt is virtually impossible to discharge in bankruptcy.

The highest level of SLABS issuance occurred between 2005 and 2007—while falling sharply during the 2008 financial crisis. Could a future recession lead to a similar breakdown in the SLABS market?

Parallels to the reckless and illegal actions of Wall Street with Mortgage-Backed-Securities (MBS) that led to the global financial crisis a decade ago may trigger similar alarm bells. Nonetheless, there are important differences between SLABS and MBS.

First and foremost, student loans cannot be collateralized. With MBS, the loans were collateralized by the house or property being purchased, but the 'equity' in student loans is the borrower's future expected earnings, which are difficult to quantify. Secondly, the overall market for SLABS is a fraction the size of the MBS market before the financial crisis. Finally, because of federal guarantees for FFEL loans and the 2005 bankruptcy laws, it is uncommon that the student loan companies will lose the value of their underlying investment, even when trends are showing that students are increasingly unable to pay their loans.

While SLABS may not pose the same level of systemic threat to the global financial system that MBS posed, there are legitimate concerns that this market poses serious systemic risks.

Navient is the largest student loan servicing company and the largest issuer of SLABS. In filings with the SEC, Navient acknowledges the following risk factors: 'An economic downturn may cause the market for auction rate notes to cease to exist… Holders of auction rate securities may be unable to sell their securities and may experience a potentially significant loss of market value.'

Due to the 'securitization food chain', if Navient or other SLABS issuers and holders experience a significant loss of revenue, they could default on their obligations—triggering negative consequences for Wall Street firms that market these securities to investors and supply credit to the greater public.

There are a few different ways this could happen. SLABS are created in a way that minimizes risk by spreading it around, but if significant numbers of student debtors default on their loans, the securities could lose their value if rating agencies downgrade them. Another possibility is that federal bankruptcy reform could favor student borrowers—which would certainly affect the market for SLABS.

Some Democratic presidential candidates have proposed significant policies to cancel student debt—Bernie Sanders' plan would cancel all $1.6 trillion of outstanding student debt, while Elizabeth Warren's plan would cancel up to $50,000 of student debt for 42 million Americans. These policies would make it less likely that the SLABS that have been issued would ever fully pay out, especially given that many of them will not reach their final maturity for decades.

Debt strikes

The student debt crisis is symptomatic of an unsustainable capitalist system. In the past several decades, the securitization of debt has become central to economic growth, but at what cost? As economist Michael Hudson has argued, 'debts that can't be paid, won't be paid', and the insistence of creditors to collect on those debts can trigger social unrest.

As the rational discontent of younger generations continues to grow, catalyzed by a lower quality of life than older generations, the accelerating climate crisis, and insurmountable student debt—activists may choose to utilize 'the power of economic withdrawal.'

Rather than endure the Sisyphean burden of unpayable debt, young people could exploit the vulnerabilities of the SLABS market via debt strikes or boycotts, as advocated during the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. Fear about the consequences of default may keep American student debtors from organizing such a strike, but greater public awareness about SLABS and the acceleration of present crises may incite more radical action.

'For thousands of years, the struggle between rich and poor has largely taken the form of conflicts between creditors and debtors', writes David Graeber in his comprehensive 2011 book Debt: The First 5000 Years. 'By the same token, for the last five thousand years, with remarkable regularity, popular insurrections have begun the same way: with the ritual destruction of the debt records-tablets.'

Activists concerned about student debt should ask themselves: what would such a symbolic protest look like in the United States today, and could it become popular enough to pose a significant threat to the status quo?

Slightly more than one in five US college students, 21.2%, admitted to financing cryptocurrency purchases with student-loan funds, a study by The Student Loan Report found.

The funds were supposed to cover students living expenses at college. Instead, they were being used to buy virtual currencies, such as Ethereum (ETH) and Bitcoin (BTC).

The study carried out a survey of 1,000 current college students with loan debt with a single question: 'Have you ever used student loan money to invest in cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin?'

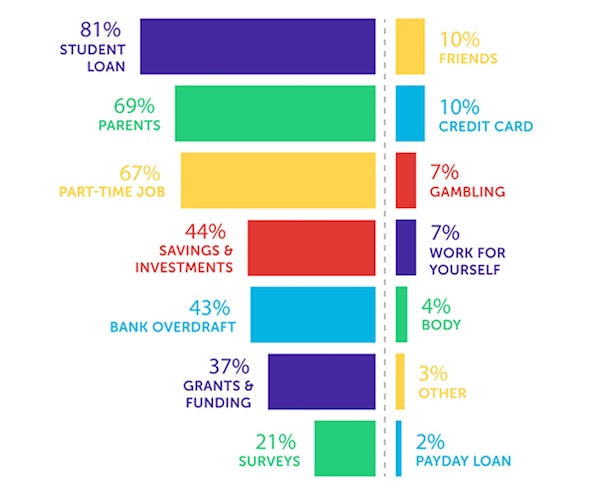

Use Of Student Loan Money

The survey did not ask how much students were investing, and many could be simply testing the waters by buying only smaller amounts.

Depending on their financial needs, undergraduate students can receive up to $5,500 in federal loans in the 2017-2018 academic year, according to Federal Student Aid, a part of the US Department of Education.

Last year, cryptocurrency growth was phenomenal and clearly this could be one the reasons for students to venture into the digital asset.

However, cryptocurrency speculation is dangerous because it exposes both borrowers and lenders to an extremely volatile market. The most popular cryptocurrency; Bitcoin rose to an all-time high price of around $19,205.11 (£13,502.92) on 17 December 2017 then dropped to a low of $6,701.40 (£4,711.69) a little over four months later on 5 April 2018, Coinbase data indicates.

The second most popular cryptocurrency, Ethereum, lost more than two-thirds of its value during the first quarter of 2018. Ethereum was trading at $1,338.67 (£941.21) on 13 January 2018 and $503.01 (£353.66) on 17 April 2018. Coinbase estimated that Ethereum's price increased by 940.14% in the 12 months that ended on 17 April 2018.

The risk to lenders is tremendous because around 44 million Americans owed around $1.48 trillion (£1.04 trillion) in January 2018, Student Loan Heroreported. The average American college student owed $37,127 (£26,103.62) in student loans upon graduation. That amount increased by 6% between 2016 and 2017. The amount of student loan debt owed in the United States exceeds credit card debts which were estimated at $1.03 trillion (£720 billion) in January 2018.

No oversights of student loans

The students are able to speculate in cryptocurrencies because there is no oversight on how the loan money is used, StudentLoans.net revealed.

In the United States, lenders send colleges a lump sum of money to cover tuition. If the funds paid out exceed the amount of tuition, the leftover cash is given directly to the students.

The students can use the funds for whatever they want including holiday trips, beer, gambling, speculation, video games, or new cars.

Disturbingly, buying cryptocurrency might be the most responsible use students are making of that money. There is at least a possibility the students might make a profit from the digital currency. Funds spent for beer or holiday trips will be completely lost.

Risks to the greater economy

Gambling With Student Loan Money Market

Corporations such as Navient, Nelnet, and PHEAA service outstanding student debt on behalf of the Department of Education. These companies also issue Student Loan Asset-Backed Securities (SLABS) in collaboration with major financial institutions like Wells Fargo, JP Morgan, and Goldman Sachs. For these firms and their creditors, debt isn't just an asset, it's their bottom line.

Investors holding SLABS are entitled to coupon payments at regular intervals until the security reaches final maturity, or they can trade the assets in speculative secondary markets. There is even a forum where SLABS investors can anonymously discuss their assets and transactions, free from unwanted public scrutiny.

Yet the financialization of student debt is almost never reported on in the media. There is little public awareness that when student borrowers sign their Master Promissory Notes (affirming that they will repay their loans and 'reasonable collection costs'), their debts may be securitized and sold to investors.

The history of SLABS

SLABS resulted from specific federal policy decisions. On November 27, 1992, the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted Rule 3(a)(7) of the Investment Company Act of 1940, which allows companies who issue asset backed securities to be exempt from the legal definition of an 'investment company.' This exemption permits companies to avoid asset registration fees and regulatory oversight—making it profitable for student loan companies (among others) to issue securities, which effectively created the market for SLABS. In total, $600 billion worth of SLABS have been issued, with $170 billion worth still outstanding.

There are two main types of SLABS: those backed by loans made by private lenders, and those backed by loans made through the Federal Family Education Loan program (FFEL). The majority of all student debt today is the $1.1 trillion loaned by the federal government through the Direct Lending program. While these loans cannot be securitized directly, they can be if borrowers consolidate or refinance their loans through a private lender.

Private student loan debt accounts for roughly $120 billion of the $1.6 trillion total outstanding debt. Companies such as SoFi refinance student loans, and have issued $18 billion in SLABS since their founding in 2011. These loans are highly favorable to lenders—as borrowers who default on private loans face greater consequences than those who default on federal loans.

FFEL loans are made by private lenders that are guaranteed by the federal government if borrowers default, which incentivizes riskier lending. Although Congress ended the program in 2010, there are still roughly $280 billion of FFEL loans outstanding, and the largest firms such as Navient and Nelnet retain FFEL loans in their portfolios and have continued to issue FFEL-backed SLABS.

The next bubble?

Over the past few decades, student loan companies and Wall Street have amassed record profits. Meanwhile, $1.6 trillion of student debt is crushing generations of Americans by delaying home ownership, causing generational wealth to decrease, and contributing to widespread depression and even suicide. Since the ironically-named Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005, student debt is virtually impossible to discharge in bankruptcy.

The highest level of SLABS issuance occurred between 2005 and 2007—while falling sharply during the 2008 financial crisis. Could a future recession lead to a similar breakdown in the SLABS market?

Parallels to the reckless and illegal actions of Wall Street with Mortgage-Backed-Securities (MBS) that led to the global financial crisis a decade ago may trigger similar alarm bells. Nonetheless, there are important differences between SLABS and MBS.

First and foremost, student loans cannot be collateralized. With MBS, the loans were collateralized by the house or property being purchased, but the 'equity' in student loans is the borrower's future expected earnings, which are difficult to quantify. Secondly, the overall market for SLABS is a fraction the size of the MBS market before the financial crisis. Finally, because of federal guarantees for FFEL loans and the 2005 bankruptcy laws, it is uncommon that the student loan companies will lose the value of their underlying investment, even when trends are showing that students are increasingly unable to pay their loans.

While SLABS may not pose the same level of systemic threat to the global financial system that MBS posed, there are legitimate concerns that this market poses serious systemic risks.

Navient is the largest student loan servicing company and the largest issuer of SLABS. In filings with the SEC, Navient acknowledges the following risk factors: 'An economic downturn may cause the market for auction rate notes to cease to exist… Holders of auction rate securities may be unable to sell their securities and may experience a potentially significant loss of market value.'

Due to the 'securitization food chain', if Navient or other SLABS issuers and holders experience a significant loss of revenue, they could default on their obligations—triggering negative consequences for Wall Street firms that market these securities to investors and supply credit to the greater public.

There are a few different ways this could happen. SLABS are created in a way that minimizes risk by spreading it around, but if significant numbers of student debtors default on their loans, the securities could lose their value if rating agencies downgrade them. Another possibility is that federal bankruptcy reform could favor student borrowers—which would certainly affect the market for SLABS.

Some Democratic presidential candidates have proposed significant policies to cancel student debt—Bernie Sanders' plan would cancel all $1.6 trillion of outstanding student debt, while Elizabeth Warren's plan would cancel up to $50,000 of student debt for 42 million Americans. These policies would make it less likely that the SLABS that have been issued would ever fully pay out, especially given that many of them will not reach their final maturity for decades.

Debt strikes

The student debt crisis is symptomatic of an unsustainable capitalist system. In the past several decades, the securitization of debt has become central to economic growth, but at what cost? As economist Michael Hudson has argued, 'debts that can't be paid, won't be paid', and the insistence of creditors to collect on those debts can trigger social unrest.

As the rational discontent of younger generations continues to grow, catalyzed by a lower quality of life than older generations, the accelerating climate crisis, and insurmountable student debt—activists may choose to utilize 'the power of economic withdrawal.'

Rather than endure the Sisyphean burden of unpayable debt, young people could exploit the vulnerabilities of the SLABS market via debt strikes or boycotts, as advocated during the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011. Fear about the consequences of default may keep American student debtors from organizing such a strike, but greater public awareness about SLABS and the acceleration of present crises may incite more radical action.

'For thousands of years, the struggle between rich and poor has largely taken the form of conflicts between creditors and debtors', writes David Graeber in his comprehensive 2011 book Debt: The First 5000 Years. 'By the same token, for the last five thousand years, with remarkable regularity, popular insurrections have begun the same way: with the ritual destruction of the debt records-tablets.'

Activists concerned about student debt should ask themselves: what would such a symbolic protest look like in the United States today, and could it become popular enough to pose a significant threat to the status quo?

Slightly more than one in five US college students, 21.2%, admitted to financing cryptocurrency purchases with student-loan funds, a study by The Student Loan Report found.

The funds were supposed to cover students living expenses at college. Instead, they were being used to buy virtual currencies, such as Ethereum (ETH) and Bitcoin (BTC).

The study carried out a survey of 1,000 current college students with loan debt with a single question: 'Have you ever used student loan money to invest in cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin?'

Use Of Student Loan Money

The survey did not ask how much students were investing, and many could be simply testing the waters by buying only smaller amounts.

Depending on their financial needs, undergraduate students can receive up to $5,500 in federal loans in the 2017-2018 academic year, according to Federal Student Aid, a part of the US Department of Education.

Last year, cryptocurrency growth was phenomenal and clearly this could be one the reasons for students to venture into the digital asset.

However, cryptocurrency speculation is dangerous because it exposes both borrowers and lenders to an extremely volatile market. The most popular cryptocurrency; Bitcoin rose to an all-time high price of around $19,205.11 (£13,502.92) on 17 December 2017 then dropped to a low of $6,701.40 (£4,711.69) a little over four months later on 5 April 2018, Coinbase data indicates.

The second most popular cryptocurrency, Ethereum, lost more than two-thirds of its value during the first quarter of 2018. Ethereum was trading at $1,338.67 (£941.21) on 13 January 2018 and $503.01 (£353.66) on 17 April 2018. Coinbase estimated that Ethereum's price increased by 940.14% in the 12 months that ended on 17 April 2018.

The risk to lenders is tremendous because around 44 million Americans owed around $1.48 trillion (£1.04 trillion) in January 2018, Student Loan Heroreported. The average American college student owed $37,127 (£26,103.62) in student loans upon graduation. That amount increased by 6% between 2016 and 2017. The amount of student loan debt owed in the United States exceeds credit card debts which were estimated at $1.03 trillion (£720 billion) in January 2018.

No oversights of student loans

The students are able to speculate in cryptocurrencies because there is no oversight on how the loan money is used, StudentLoans.net revealed.

In the United States, lenders send colleges a lump sum of money to cover tuition. If the funds paid out exceed the amount of tuition, the leftover cash is given directly to the students.

The students can use the funds for whatever they want including holiday trips, beer, gambling, speculation, video games, or new cars.

Disturbingly, buying cryptocurrency might be the most responsible use students are making of that money. There is at least a possibility the students might make a profit from the digital currency. Funds spent for beer or holiday trips will be completely lost.

Risks to the greater economy

The student loan situation will remind many observers of the US subprime mortgage crisis of the mid-2000s.

That crisis developed because of irresponsible lending to low-income individuals many of whom used the mortgage money borrowed for other purposes. Some borrowers used second mortgages to cover living expenses or finance holidays, and calls. Many people used the subprime mortgages to speculate in real estate – the infamous flipping.

The subprime crisis was one of the underlying causes of the financial crisis of 2007 to 2008. That crisis developed because investment banks, hedge funds, and other financial institutions were heavily-invested in mortgage-backed securities.

The student loan market is already in crisis, around 11.5% of student loans were in default in October 2017, US Department of Education data indicates. The number of student loans in default was estimated 8.5 million and the number of loans in default increased by 12% between June 2016 and June 2017, Forbesreported.

Technology fuelling speculation

The exposure of the economy and individuals to volatile speculative markets is greater than ever because of new financial technologies such as cryptocurrencies. The student loan situation reveals that individuals at all levels of the economy are exposed to the cryptocurrency risks.

The amount invested in cryptocurrencies is now large enough to create risks for the wider economy. The total market capitalization of all cryptocurrencies reached $741.620 billion (£521.43 billion) on 8 January 2018, CoinMarketCapcalculated. That figure fell to $257.704 billion (£181.19 billion) by 4 April 2018. That means cryptocurrency lost nearly $500 billion (£351.55 billion) in value in four months.

Exposure to new speculative investments like cryptocurrencies is a risk that all insurers and lenders will have to take into account. New technologies are greatly increasing volatility and spreading the exposure to that volatility far and wide.